Leonardo and Milano

Several stops for a tour to live and imagine Leonardo’s Milano

“Milano, you must know, is now the most affluent and bounteous city in Italy (…) The Milanese in all things they do are keen on living well, rather than on appearing (…) and to all foreigners, they are very courteous and are very happy to see them” Matteo Bandello, Novella VIII

IT’S A MATCH!

Leonardo and Milano

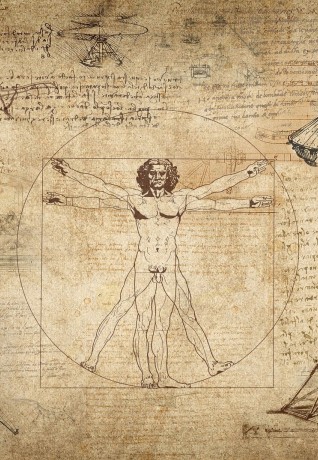

Leonardo and Milano were meant to cross paths. On the one hand, we have a multitalented artist, futuristic engineer and master of ceremonies, an accomplished painter, architect and musician. On the other, a growing city finally at peace. Its population numbered around 200 thousand and its court during the Renaissance was at the same level as that of Florence, able to attract talented people and set fashion trends and customs throughout Europe.

Only a few people know that Leonardo spent the longest and most prolific part of his life in Milano. It was his adopted hometown. What better place for a talented thirty-year-old man, schooled in Florence and now seeking fortune, prestige and a place to freely express his creativity?

In the city of Milano, Leonardo found a thriving commercial hub with a penchant for innovation. The established artistic tradition was Gothic and the Renaissance was bringing in a new style. There was a network of canals in constant development, and borders to protect - but expansion outside the walls was the main objective. There was also a Court to be amazed with extravagant pageants and two large building sites - the Castello Sforzesco and the Duomo Cathedral with its cupola needing to be completed.

He arrived in the city carrying a silver lyre-shaped like a horse's skull in his apprentice's bag. He’d designed it himself and could play it magnificently: the instrument was a gift for the Duke of Milano, Ludovico Maria Sforza. At the age of 30 - just like Leonardo - the Duke was a military leader and patron of artists and scientists, and he was transforming his court-fortress into an icon of style: the two men openly shared a passion for things at once beautiful and useful.

Before the Last Supper, the projects for the canals, the drawings of the Duomo cupola or his flying machines, Leonardo submitted to the Duke of Milano Ludovico il Moro a project for a bronze horse as a tribute to the Duke’s father, Francesco Sforza. This letter is actually one of the world’s first CVs!

Today, it is a fortress with three courtyards - the bustling city and its traffic and shopping districts on one side, and the green Parco Sempione on the other. When Leonardo lived in Milano, the Castello Sforzesco was the beating heart of the ideal city that a Renaissance architect and genius named Filarete had designed as an 8-pointed star, naming it Sforzinda, an image of harmony and perfection.

Leonardo walked about the Castle with his long, thick beard. At times he was impetuous, at times lost in his own thoughts: he always carried a collection of sheets on which he randomly entered notes in pencil from right to left, drawings in ink, and sketches in charcoal.

Even a young musician was immortalised by Leonardo, and this portrait is among the highlights of the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan, alongside Bruegel, Caravaggio, Tiziano and Botticelli. Not far from it, in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, the Codex Atlanticus collects 1000 of these sheets, summing up Leonardo’s thoughts, vision and projects.

Five hundred years after Leonardo lived, his studies continue to fascinate us, make us think and - most importantly - inspire. In 1953, exactly five centuries after Leonardo was born, an ancient 14th-century convent became the first science museum in Italy to be named after him: here, not far from Santa Maria delle Grazie and the Vineyard, a series of models built according to Leonardo's drawings are on display, a 3D version made of fine materials and very respectful of the artist’s idea.

Four years are really too long to paint a mural! The Duke is in a hurry: he has the most talented man in his court paint the Last Supper on the refectory walls in the convent besides Santa Maria delle Grazie.

In his Codex Atlanticus, Leonardo sketched some of the most innovative water engineering discoveries: among the many drawings, there were the “chiusini”, small underwater openings set into the doors that could be moved by hand to allow the waters to flow more slowly and prevent passing boats from being rocked and dumping their cargo when the locks finally opened. One of the locks built at the time with this mechanism can still be seen today. The place is called Conca dell’Incoronata, and it is not far from the Brera district.

The statue of Leonardo da Vinci was conceived decades before its presentation: it was started when the Austrians ruled the city, and finished shortly after the liberated city had just opened the square in front of La Scala Theatre and the façade of Palazzo Marino, the City Hall and the institutional site, was being renewed. The year was 1872, and the placing of this statue shows how Leonardo da Vinci's fame endured and survived through the centuries.

Log in

Log in